Elizabeth Hardwick (better known to history as 'Bess of Hardwick') was born in the 1520s (estimated dates range from 1520-21 to 1527), a daughter of John Hardwick of Hardwick, Derbyshire, a member of the minor gentry, and his wife Elizabeth Leake. Bess's father John died in 1528, leaving behind a young family: his widow, son and heir James, and 5 daughters (including Bess, who was likely the second daughter) (Hubbard, 2018).

It appears that the family continued to reside at Hardwick, which was being rented to John's widow, as it had been returned to the Crown on his death, despite his will requesting that it be put in trust for his son James (Lovell, 2005). Faced with increasing financial and social stressors, Elizabeth remarried, and had further children with her new husband Ralph Leche; however, this marriage brought many problems, with Leche reportedly running up debts in purchasing wardships and leaseholds, which led him to be imprisoned at the Fleet Prison, as well as reports of him deserting his wife and children (Lovell, 2005; Hubbard, 2018). In contrast to other contemporary female figures, Bess does not appear to have had an exceptional education; whilst she was literate, she does not appear to have been a prolific reader. Neither did she adopt the vehement Protestant Reformist views of some of her peers, which included the Dorsets, with whom she would have joined in prayer daily the two years she was placed within their household (Hubbard, 2018).

Bess was married and widowed young, to Robert Barley/Barlow, a teenager, approximately 14 years old, of another Derbyshire family, in a mutually financially beneficial arrangement. Hubbard (2018) acknowledges that she married within the lifespan of her father-in-law (who died in 1543), but it is known that the groom died on 24 December 1544. Whilst this marriage was legal, with parental consent being given (girls over 12, boys over 14), it was likely that the marriage was never consummated.

In 1545, Bess joined the household of Frances Brandon, the Marchioness of Dorset, and wife of Henry Grey, Marquess of Grey, based primarily at Bradgate Hall, Leicestershire, as a 'waiting gentlewoman'. It was during this time that Bess had contact with the Frances' children, including Jane Grey (who was approximately 10 years younger than Bess), although Jane was sent away from Bradgate in February 1547 under the wardship of Sir Thomas Seymour. It is assumed that there was a fondness between Bess and the younger sisters, as Katherine and Mary Grey became close friends with her as they grew older (Lovell, 2005; Tallis, 2016).

Bess' time with the Dorsets was successful, with her personality making her popular amongst the family, and in court circles. It was likely that she accompanied the family to Dorset House, as Henry Grey played an important role in events in early 1547, in both the funeral of Henry VIII and the coronation of his son, Edward VI. It was when she was placed within the household, that Bess met Sir William Cavendish, Treasurer of the Chamber in the Royal Household; he was an older man (born c.1501), who was widowed with daughters. Hubbard (2018, p.17) surmises that Cavendish chose Bess not for her physical attributes, describing her as "no great beauty, but she was spirited, vital and determined...whose ambition, energy and pragmatism matched his own".

Bess and Cavendish married on 20 August 1547 at Bradgate House, Leicestershire, in a wedding hosted by the Dorsets - this was likely due to a combination of their fondness for Bess, as well as way of attempting to obtain favour with Cavendish, who in his role, had regular access to the King and Royal Household. Celebrations lasted for a further two days following the wedding ceremony which unusually took place at two o'clock in the morning, confirmed by an entry Cavendish made in his diary (Lovell, 2005).

Bess became 'Lady Cavendish', and left Frances' service; however, the pair remained close throughout their lives. The following year, Bess gave birth to her first child, a daughter named Frances; Frances Brandon was chosen to be a joint godmother, along with her stepmother Katherine Willoughby, the Dowager Duchess of Suffolk. Bess' second daughter Temperance was born in 1549; this child's godparents included Frances' daughter Jane Grey, as well as her future mother-in-law Jane Dudley (neé Guildford), Lady Warwick. Bess and William went on to have another 6 children, including son William Devonshire (the ancestor of the Dukes of Devonshire), with the couple strategically chosing godparents to purposely ally themselves with the new Protestant regime (Lovell, 2005; Hubbard, 2018).

After their marriage, William moved Bess initially to London and Northaw, Hertfordshire, where she spent time in the court of King Edward VI and the Royal Faction of the Seymours and their allies. It was these early years at court, and being exposed to educated peers, as well as the ever-changing city around her, where Bess started to develop an interest in classical architecture and design (Hubbard, 2018).

William went on to sell his property in Hertfordshire and Suffolk (former monastic lands obtained from the Dissolution of the Monasteries), with the couple moving back to Bess' native Derbyshire, where he purchased the Chatsworth estate, near Bakewell in 1549; Hubbard (2018) notes that this estate was familiar to Bess, being fomerly in the ownership of the Leche family, and that the couple were 'tipped off' for the sale of the estate by her mother and sister. Construction started on Chatsworth House in 1552, and was completed the following decade, with Bess overseeing the ambitious project. There is little of the Elizabethan Chatsworth House that was originally constructed, as it was demolished and rebuilt on the same foundations in the 17th century, apart from the cellars, hunting tower and a moated structure within the grounds (Hubbard, 2018).

William Cavendish died in 1557 (before the original Chatsworth House could be completed); Bess went on and married another two times, with her final marriage becoming 'Elizabeth Talbot, Countess of Shrewsbury'. During her final (and often fractious) marriage, her husband George Talbot, 6th Earl of Shrewsbury was appointed as the custodian of Mary, Queen of Scots for 15 years (of the her 19 years total imprisonment) from 1569; Chatsworth was one of the properties that she was held at.

Hunter (2022) identifies that the Talbots were the 'perfect' custodians for Mary, being wealthy enough to provide comfortable lodgings and security for their prisoner, demonstrating loyalty to their Queen, and being aware of their role and importance in the political sphere of the Elizabethan court. Over the years, there were many attempts made by her supporters to facilitate Mary's escape from her imprisonment, with Bess's involvement and allegiance being questioned at times (Lovell, 2005).

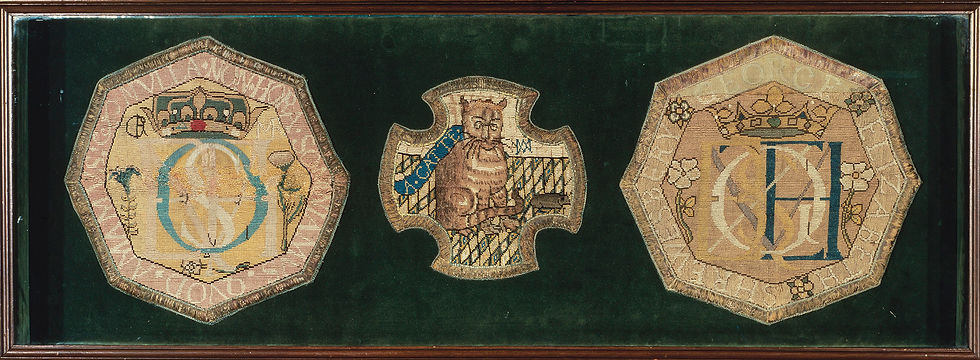

During her time in the Talbots' custody, Mary's movements, contacts and activities were restricted. However, one activity that she did participate in was embroidery; engaging in this needlework, along with Bess (who participated alongside her when on an extended visits), enabled Mary to "assert control over her existence" (Victoria and Albert Museum, 2024). The embroidered panels of canvas created were often small, easily portable, and consisted of different method of needlework, including cross-stitch. Bess, Mary and their female household embroidered over 100 panels over the years that Mary was held in the Talbots' captivity, at their various homes (including Chatsworth) with the pair often 'signing' their work with either their initials, monograms or cyphers (Victoria and Albert Museum, 2024). Despite this. the extended time Mary spent in their custody caused increased tension between the married couple, due in part to the expenditure and effort required to keep their prisoner captive (English Heritage, 2024).

Despite her relatively humble beginnings, as a result of these marriages, Bess became extremely wealthy (in the latter years of her life being the richest woman in England only after Elizabeth I), and rose high in Elizabethan society. She embarked in a series of ambitious building projects around Derbyshire in addition to Chatsworth, including 'Owlcoates' and 'Hardwick New Hall', the latter remaining one of the greatest examples of Tudor architecture, itself influencing future building projects (Hubbard, 2018).

Bess died on 13 February 1608 at Hardwick, and was buried at All Saints' Church, Derby (has since been rebuilt as Derby Cathedral); Chatsworth House passed to her second son Sir William Cavendish, who was later created the 1st Earl of Devonshire. Today, Chatsworth remains within the Cavendish family, having become the family seat of Dukes of Devonshire, the descendants of William and Bess, from 1694.

Comments