Anne Askew's name has long been associated with martyrdom in Henry VIII's Protestant England. However, her early years were not necessarily indicative of a woman who would grow up to be at the forefront of rebellion and heresy in the religiously turbulent 1540s.

Anne was born in c.1521 in Lincolnshire, the fourth child of Sir William Askew, and his first wife Elizabeth Wrottesley. William, whose family originated from Stallingborough, was a gentleman in the court of Henry VIII, had accompanied the King to Calais for the 'Field of the Cloth of Gold' in June 1520, and had been called up as a juror in the trial of the men accused of treason along with Queen Anne Boleyn in May 1536. The family (including Anne's siblings Martha, Jane, Francis and Edward) moved to South Kelsey, Lincolnshire following the death of her mother shortly after Anne's birth, and her father's remarriage, which is where Anne spent the majority of her childhood. It was whilst residing in South Kelsey that William's political career is documented - as High Sheriff of Lincolnshire and a Member of Parliament. Anne likely received a classical education, as was the norm for those of high-social status, learning to read and write; these skills would be beneficial to her later in life.

Anne's eldest sister Martha had been betrothed to Thomas Kyme, an older man from another prominent Lincolnshire family. However, Martha died in 1536, before this union could take place, leading a teenage Anne to be put forward by their father, who had arranged the match, in her stead. Whilst this marriage produced two (surviving) children, it was not a happy or successful one. Thomas was reported to be violent towards Anne, who in turn showed apparent stubbornness and insubordination by refusing to take on her husband's name, including in her writings, as was socially expected (Beilin, 1996). However, one of the primary issues that the couple clashed on were their religious beliefs; Thomas Kyme remained a Catholic, whilst Anne openly converted to the new Protestant religion.

From 1527, the Protestant Reformation which had swept Europe over the past decade (set in motion by Martin Luther publishing his 'Ninety-Five Theses', in which he challenged the perceived corruptions and abuses of the Catholic Church) came to England. However, Henry VIII initiated the break from Rome not wholly based on religious principles or beliefs, but rather for personal gain: the Pope had refused to grant him a divorce from his first wife, Catherine of Aragon (which he needed in order to marry his long-term mistress Anne Boleyn), as well as monetary gain, with the Dissolution of the Monasteries.

Whilst the separation from 'Papal Rule' in 1530, and subsequent supremacy over the Church in England was Henry's prerogative, cemented by 'The Act of Supremacy' in 1534, implementation of new religious practices was not, with the introduction of such remaining restrained throughout his rule. In spite of Henry's reluctance for progressive change, new and more extreme Protestant beliefs were beginning to sweep the country, across all the social classes, including those within Henry's own court.

Anne Askew belonged to the branch of Protestantism known as 'Reformists'; this subdivision was originally formed by the leader of the Swiss Reformation Huldyrich Zwingli of Zurich. Whilst there were similarities to the ideas initially suggested by Luther, the two famously clashed in 1529 regarding their differing beliefs about the Eucharist. Other Swiss Reformers who were influential at this time included John Calvin (who was known to have communicated with Anne Seymour, the eldest daughter of Edward Seymour, then Duke of Somerset and Lord Protector in 1549) and Zwingli''s successor Heinrich Bullinger (who was also known to have communicated with Henry Grey, Duke of Suffolk and father to Lady Jane Grey, as well as dedicating writings to him); it was this branch of Protestantism that appeared to be spreading to the upper classes and being taught to the next generation by foreign tutors.

Beilin (1996) identifies Protestant sympathies in not just Anne, but in other members of her immediate family. Whilst she would have been born and initially raised in the Catholic religion, there is evidence that William adopted the new religious ideas coming out of Europe, which in turn had an influence on his children's education and upbringing. Anne's sister Jane was married to a Protestant man, whilst their brother Edward was a member of Archbishop of Canterbury Thomas Cranmer's household, Cranmer being responsible for the introduction of the new doctrinal structures of the English Church and viewed as a leader of the Protestant Reformation in England. William himself came to the King Council's attention in his political roles in Lincolnshire, where judgments were made which appeared to show his Protestant leanings (Beilin, 1996).

Henry VIII's new Queen, his sixth wife Katherine Parr, was also amongst the growing number of Protestant Reformers. In 1544, anonymously, she published her first book 'Psalms and Prayers', and the following year published her second 'Prayers and Meditations', this time proudly putting her name to the religious text. Katherine also surrounded herself with ladies in her court who shared similar religious beliefs; these included Katherine Willoughby [Brandon], Dowager Duchess of Suffolk, Anne Stanhope [Seymour], Lady Hertford, and Jane Guildford [Dudley], Viscountess Lisle. The potential influence of these women on the Queen, as well as their husbands and immediate families (including Edward and Thomas Seymour, uncles to Prince Edward) had long caused concern from a 'conservative faction' at court, led by Stephen Gardiner, Bishop of Winchester, who were concerned that she was being encouraged to persuade the King to adopt new religious practices (Weir, 1991; Paul, 2022).

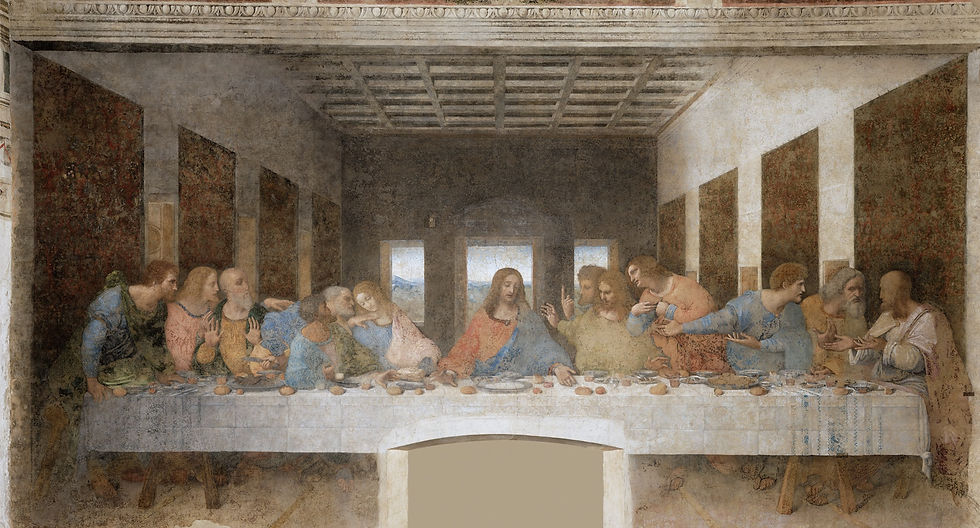

Traditionally, the Catholic Church taught that there were seven rites or 'sacraments' during which God could communicate his grace, and which were essential for salvation, that being the deliverance of the soul from sin. Holy Communion or the Eucharist is one of these sacraments; the rite invoked by Jesus at the Last Supper the night before his crucifixion, giving his disciples bread and wine. The Catholic Church believe that during the Eucharist, with the giving of unleavened bread and wine by priests, that there is a physical change, and they become the body and blood of Jesus Christ, by the act of transubstantiation. Challenging and rejecting these long-held beliefs were at the core of the Protestant reformation. However, the various religious factions that quickly formed could not reach an agreement in their beliefs regarding the Eucharist, despite the other revolutionary ideas that were developing. Luther's followers adopted the idea of consubstantiation - the belief that during the Eucharist the bread and wine co-exist with the body and blood of Christ - whilst Zwingli's Reformists believed that there is no physical presence, and that only the Holy Spirit is present at this time. Anne, having been taught, adopting and then preaching to others the teachings of Zwingli and his subsequent rejection of transubstantiation, placed herself in danger given its conflicting views with the English Church's official stance. In 1539, Parliament passed 'The Act of Six Articles', in which it reaffirmed some of the fundamental aspects of the Catholic Church, transubstantiation being one of these. Denial and rejection of these beliefs could now legally be defined as heresy, which could be punishable by death, with those convicted suffering 'paynes of death by way of burninge' (Beilin, 1996; Paul, 2022).

In May 1543, another Act of Parliament was passed: 'The Act for the Advance-ment of true Religion'. This was intended as an attempt to reduce the possession of William Tyndale's 'Bible', the New Testament of which had been translated into English from Hebrew and Greek, and published in full in 1535 by Myles Coverdale, and subsequently the discussions which accompanied it, including that related to the Eucharist. The Act placed restrictions on the reading of the Bible: those belonging to the clergy, nobility, gentry and other upper classes were permitted to read authorised copies (i.e. not Tyndale's translation), with only the clergy permitted to read in public. Women (below the gentry class) and all those of lower classes, including servants, apprentices and the poor, were banned from possession and reading of the Bible. Anyone who was caught flaunting these laws, from those publishing banned works and those in possession, would be punished (by way of fines, possession property or imprisonment). The Act also restricted the readings and preaching of the Bible and other scriptures "in any churche or open assemblye", with anyone found to have breached these new laws threatened with imprisonment (Eyre and Strahan, 1817, pp.894-7). As a member of gentry, Anne was permitted under this new law to continue to be in possession of the Bible and to read it in the privacy of her own home, something that was not afforded to her future friend Joan Boucher; however, it was in response to these new limitations, that Anne started openly expressing her Protestant beliefs, and reading from the Bible in public, sharing her knowledge of the scriptures to those whose access had been limited (Norton, 2016).

Anne's marriage had certainly broken down by this time, with the ongoing conflict regarding their religious beliefs, along with Anne openly opposing the laws related to religious practice. Beilin (1996) notes contemporary sources that suggest that Anne was seeking a divorce from Thomas Kyme - that it is possible she initially went to the bishop's court in Lincoln, and when unsuccessful, to the Court of Chancery in London. Weir (1991, p.512) notes that Anne applied the King for legal separation from Kyme, after he had "thrown her out of doors", and prevented her from having any contact with her two children. It was following this banishment from her home that Anne moved to London in c.1544.

Anne found London more welcoming than Lincolnshire, in regards to the support for her and her Reformist beliefs. On her arrival to London, she was introduced to other Protestants and their sympathisers, including Anabaptist Joan Bocher (who would later receive the same fate, being executed for heresy in 1550) and John Lascelles (who would be tried and executed with her). With her good family connections, Anne was able to obtain an audience with King Henry VIII, in which she applied to him for legal separation from her husband (which was denied). However, it was her ongoing preaching and reading from the Bible to others (which earned her the sobriquet of 'The Faire Gospeller'), in addition to her outspoken beliefs 'against the sacrament' (i.e. denying transubstantiation) which gained the attention of the authorities.

Anne was first arrested in London on 10 March 1545, and appeared at Saddler's Hall later that month, when she was arraigned for speaking 'against the sacrament'. Despite her boldly expressing her views relating to the Eucharist, no witnesses came forward to support the charge, and so she was discharged with a fine, much to the frustration of authorities (Beilin, 1996; Norton, 2016). Her estranged husband, Thomas Kyme, who was instrumental in her arrest, ordered Anne to return to Lincolnshire; however, she continued to rebel, and returned to London where she obstinately continued her preaching.

Whilst she was held at Newgate Prison in 1545, Anne composed her 'Ballad', which was later published, making her one of the first women to have their original work published in English. Another poem, 'I Am A Woman Poor and Blind' speaks of her personal turmoil and resolution in her mission to continue to spread the Protestant ideas to others (PoemHunter, 2024). 'A Prayer of Anne Askew' which she reportedly wrote just prior to her execution was later published in 'Foxe's Book of Martyrs'.

Following another detention in early 1546, Anne was arrested for the third and final time in May 1546, which appears to have been instigated by her estranged husband. Both Anne and Thomas Kyme were ordered to present themselves infront of the Privy Council at Greenwich Palace for questioning. Those present included Stephen Gardiner, Bishop of Winchester, and Thomas Wriothesley, Henry VIII's Lord Chancellor. Anne later wrote that she was initially questioned on that first day for five hours, including on her opinion on 'the sacrament' (Eucharist). The following day, Anne was ordered once again to present to the Council, which now included John Dudley, Viscount Lisle and Lord High Admiral, and William Parr, Earl of Essex and younger brother of Queen Katherine. There was hope from Bishop Gardiner that the presence of Dudley and Parr, both of whom were known to have Protestant sympathies, would lead to Anne recanting on her statements; however, they remained unsuccessful, and she continued to express her fixed beliefs (Paul, 2022).

Following this initial questioning, Anne was taken to Newgate Prison. It was from there that she was taken back to the city's Guildhall for her arraignment - the date was recorded by a witness as being 18 June 1546, although an alternative date of 28 June 1546 has been offered. Anne, along with three men, were arrained on charges of heresy; all confessed their guilt, and without the need for a trial and were found guilty of heresy, and condemned to death by burning. Anne later recorded the events of her arraignment, in which she denied that she was a heretic, or felt that she deserved a death sentence, although commented "I neither wish death, nor yet fear his might". However, she continued to challenge the belief of transubstantiation, reaffirming "...as for that ye call your God, it is a piece of bread" (Catterley, 1838, p.546). After this hearing, Anne was returned to Newgate Prison.

Following her conviction, permission was given for Anne to be moved to the Tower of London, for the purposes of 'examination, after further attempts to encourage her to recant her beliefs had failed (Norton, 2016)'. Thomas Wriothesley, who had remained a staunch Catholic, was one of those who opposed Queen Katherine and her allies, and so was looking for an opportunity to challenge his openly Protestant enemies (which included the Seymours), and therefore reduce their influence on the Royal Household; they would be the focus of Wriothesley's interrogation (Weir, 1991). The King had inaccurately been informed that Anne had personal connections with his wife; based on this, Henry gave permission for torture to be used, as a means of gathering information, specifically related to the Queen, her ladies, and their alleged sympathies with Reformists. This was a bold decision from Henry, as torture was not permitted except where treason was suspected, and Anne's privileged background should have made her exempt from this (Paul, 2022). In fact, Anne is the only woman on record to have been subjected to torture at the Tower.

Anne was moved from Newgate Prison to the Tower of London, on 29 June 1540, where she was subject to torture by use of 'the rack', the primary instrument of torture within the Tower (Historic Royal Palaces). Thomas Wriothesley conducted Anne's 'interrogation', whilst Sir Richard Rich, Speaker of the House of Commons, conducted the 'examination'. Initially she was asked "if I knew any man or woman in my sect" (Catterley, 1838, p.547), asking specifically about ladies within Queen Katherine's household. Anne writes in her own version of the 'Examinations' that she had denied knowing any, but confirmed that she had received monetary gifts from gentleman whilst in Newgate said to have been courtesy of Anne Stanhope [Seymour] and another lady-in-waiting to the Queen. Anne reports that following these questions, she was then placed on the rack, located in a dungeon in the Tower. As described by Paul (2022), Anne would have lay down in a supine position on the rack, with her arms and legs spread out, which were bound with rope. Poles that were inserted into the axles of the device enabled it to be turned, causing the ropes tied around her wrists and ankles to be 'wrenched', slowly and painfully pulling her limbs from their sockets, all whilst being questioned. Repeated wrenching on the rack would cause increased agony, and sometimes the threat of this would be enough for prisoners' "resolve" to break (Historic Royal Palaces). Once on the rack, the questioning shifted attention to Queen Katherine, as well as members of the King's Council; however, Anne continued to deny any personal contact or knowledge of any 'traitors' or 'heretics' (Paul, 2022).

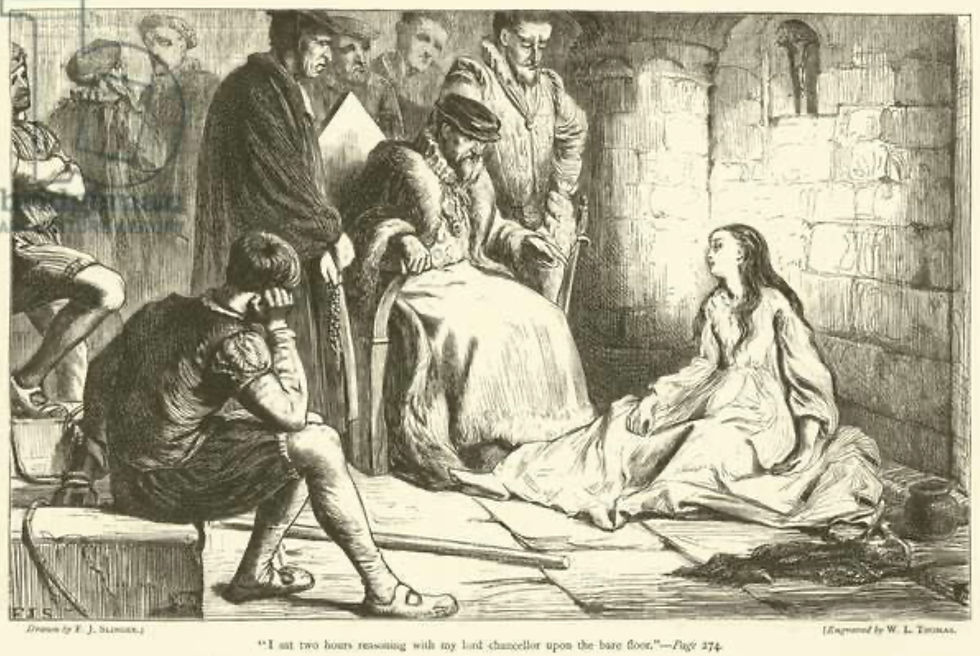

Whilst the Tower's Lieutenant Sir Anthony Knyvett initially oversaw the use of the rack, he soon protested to the repeated racking, and refused the orders of Wriothesley, leading the two men to continue themselves. Anne confirmed repeated wrenching, later writing "they kept me a long time...because I lay still, and did not cry, my lord chancellor and Master Rich took pains to rack me with their own hands until I was nigh dead" (Catterley, 1838, p.547). Anne confirmed that after being released from the rack, she "swooned" before recovering, and then being subject to further interrogation whilst on the floor, by Thomas Wriothesley, including related to her own 'heretical' beliefs. Anne was then transferred from the Tower, to a private residence, to aid her in her recovery. However, questions were still being asked of her, relating to the Queen, her household, and Anne's own outspoken beliefs. Anne continued in her stance of not revealing any damning information, despite the threat of 'burning', commenting "I sent him [Wriothesley] again word, that I would rather die, than break my faith (Catterley, 1838, p.547); she was subsequently sent back to Newgate Prison to await her fate.

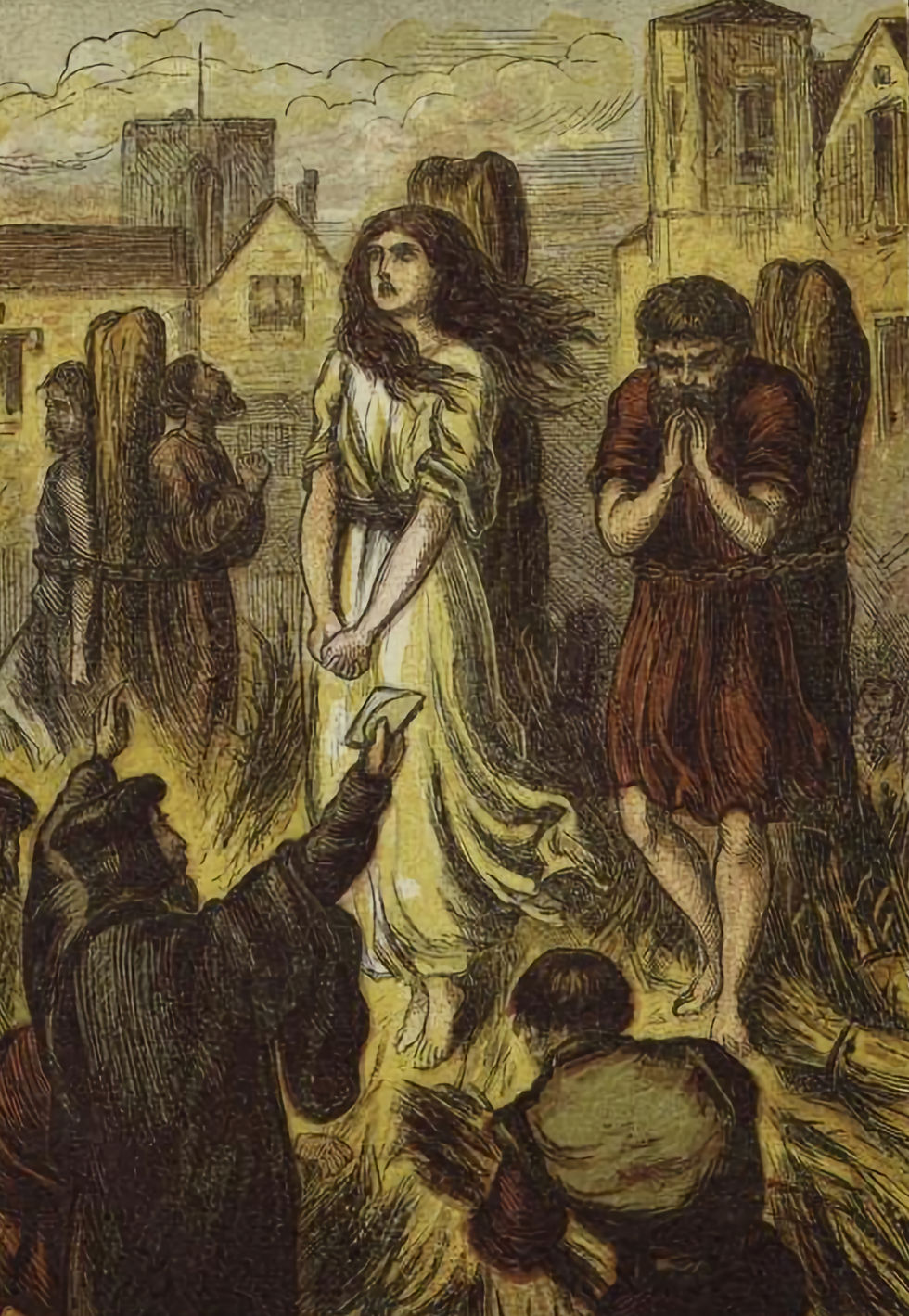

On 16 July 1546, Anne was taken from Newgate Prison to nearby Smithfield Marketplace, the chosen place for her execution. Due to the injuries, including multiple limb dislocations, that she had sustained as a result of the torture at the Tower, she was unable to walk ('lamed upon the rack') and so was carried to the site in a chair (Catterley, 1838). Once at the marketplace, Anne was dragged from the chair and tied to a stake, with a chain around her middle, to hold her up. She was accompanied by three men, all of whom had also been convicted of heresy and condemned to death: John Lascelles, Nicholas Berenian and John Adams, all being tied to stakes erected on the same pyre (Norton, 2016). A platform had been erected in the marketplace, outside St Bartholomew's Church, for those of importance who attended the execution; these incuded Thomas Wriothesley himself, as well as John Russell, 1st Earl of Bedford. Bags of gunpowder were around the necks of the condemned by the executioners, in an attempt to speed up their deaths "in an attempt to rid them of their pain" (Catterley, 1838, p.550). John Foxe wrote that before the fire was lit, Wriothesley produced letters offering the King's Pardon to Anne and the men, if they were to recant their statements; however, all refused, and so the pyre was lit and in front of a large crowd, the death sentences were carried out.

Following Anne's execution, her commitment and tenacity to the Protestant cause made many sympathisers view her as a martyr. Transcripts of her testimonies of her multiple 'examinations' in Jun 1546 were quickly edited by John Bale,. and published as 'The Examinations of Anne Askew', whilst Anne's story and words later were featured in John Foxe's 'The Actes and Monuments of these Latter and Perilous Days, Touching Matters of the Church' (otherwise known as 'Foxe's Book of Martyrs'), which was first published in 1563. Both of these texts were popular in these turbulent years, with Anne's influence continuing after her death. These texts were published once again in the mid-19th century, with Victorians taking an interest in their country's history. The rack continued to be used at the Tower of London as an instrument of 'interrogation' and torture throughout the 16th century, and into the 17th century, in particular for those suspected to be guilty of high treason. Whilst not recorded, it is suspected that Guy Fawkes was racked, following his arrest for his involvement in 'The Gunpowder Plot' in November 1605, in an attempt to give the names of his co-conspirators; his signature before and after his time at the Tower suggesting evidence of torture (Historic Royal Palaces, 2024).

The notoriety of the rack was also immortalised in many of William Shakespeare's plays, written at the end of the 16th and beginning of the 17th century, including 'The Merchant of Venice' (c.1596), 'Othello' (c.1603) and 'King Lear' (1606):

BASSANIO: Let me choose, For as I am, I die upon the rack. PORTIA: Upon the rack, Bassanio? Then confess What treason there is mingled with your love. The Merchant of Venice. Act III; Scene II.

OTHELLO: Avaunt! Be gone! Thou hast set me on the rack. I swear 'tis better to be much abused Than but to know 't a little. Othello. Act III; Scene II.

KENT: ...That would upon the rack of this tough world Stretch him out longer. King Lear. Act V; Scene III.

Comments